With everyone at the bottom of this gravity well called Earth, getting anything into space requires a massive amount of effort and energy.

That said, we lucked out!

Earth sits in what you might call a Goldilocks gravity well: deep enough to hold onto an atmosphere and oceans, yet shallow enough that we can climb out of it with rockets. To escape Earth’s pull entirely requires a velocity of about 11.2 km/s, while reaching orbit needs roughly 7.8 km/s. That is equivalent to burning through nine-tenths of your rocket mass in propellant just to reach an altitude of a few hundred kilometers. That is a brutally steep climb and it pushes our launch systems to the theoretical limit of what chemical energy can supply.

Had Earth been a bit larger its escape velocity would exceed what even the most efficient chemical propellants (liquid hydrogen and oxygen) can generate enough delta-v to break free with useful payloads. A world only slightly smaller, by contrast, would lose its atmosphere and water to space well before any species can dream of building rockets. We happen to live on the kind of planet that is just massive enough to live on and just small enough to leave. A cosmic sweet spot that makes spaceflight hard, but possible.

Payload fraction

One of the most important metrics for a rocket is the payload fraction, the amount of useful mass that can be brought to space. This efficiency indicator is the hard cap driven by Earth's gravity well and it shows how much rocket and fuel you need to get a kilogram of useful mass to the right orbit. That fraction drops the closer you get to Earth escape and several of the rockets currently operating can't even make it to higher energy orbits.

The SpaceX workhorse Falcon9 has a 3.2% fraction to LEO, dropping to 0.6% for Earth escape. The Falcon Heavy has increased capacity at 4.2% to LEO and 1.2% to escape, while Starship is currently projected to achieve about 2% to LEO. While that last launch brings a lot more mass to LEO, it can't get to Earth escape.

Other commercial rockets achieve broadly similar ranges, which has kept the cost of launching stuff to orbit high and climbing in the last decade.

Launch cost

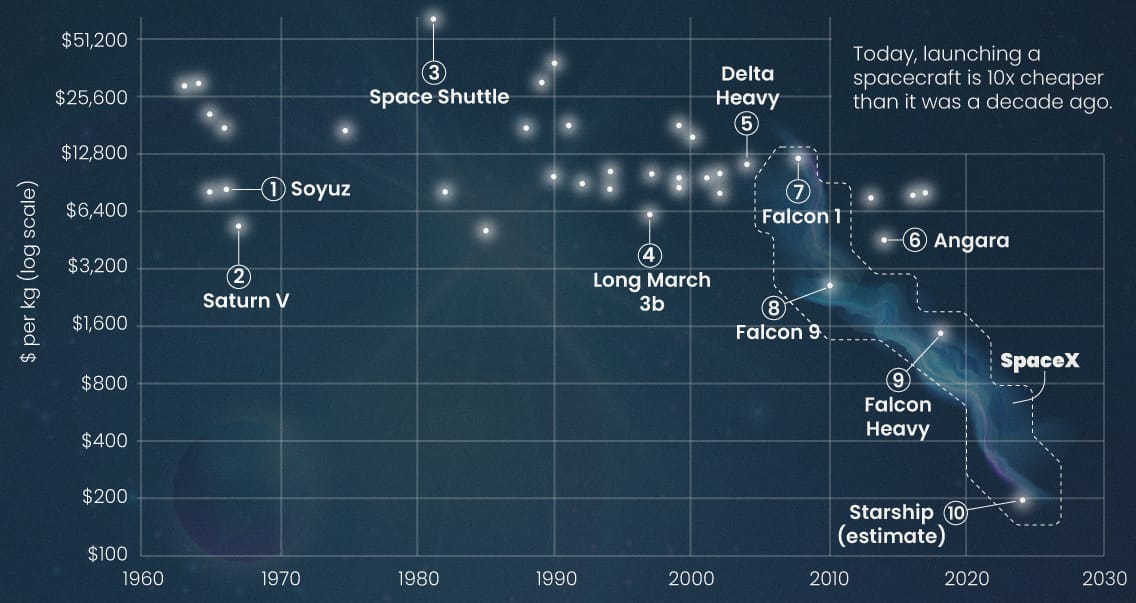

This graph is probably the most misunderstood and misquoted representation of the space market in the last 2 decades. It shows this compelling downward slope on launch cost, which does not track with reality at all:

If you talk to anyone actually buying launches today, it looks like this:

This post is for subscribers on the K+ in depth tier only.

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.