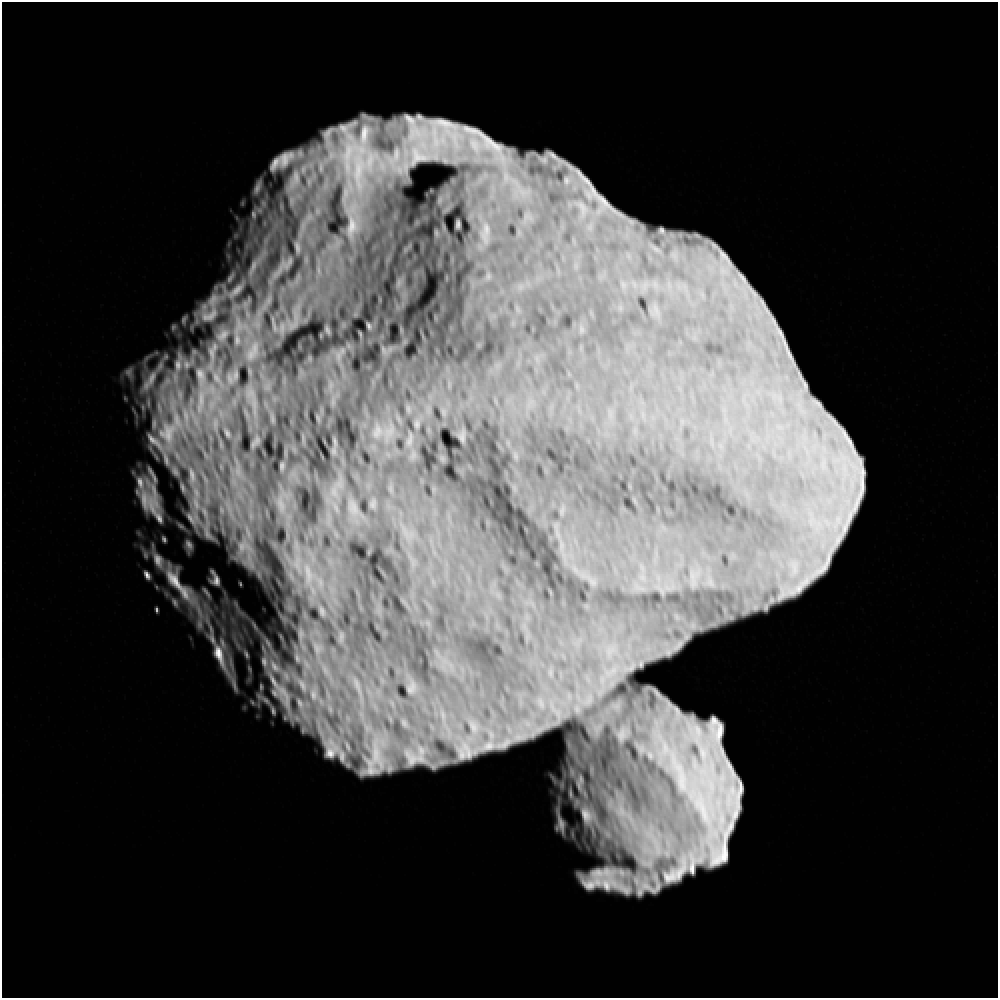

Binary asteroid 152830 Dinkinesh (Dinky) as captured by spacecraft Lucy on a flyby

NASA's Lucy spacecraft is on a 12-year journey in which it will perform flyby encounters with at least 2 main belt and 6 Jupiter trojan asteroids. In November of 2023, one of its targets called 152830 Dinkinesh (we like its nickname Dinky better) finally resolved from a series of pixels to something more accurate.

Dinky is the smallest main belt asteroid that has ever been visited, with an estimated diameter of ~720 meters. Lucy is carrying a pretty decent camera called L’LORRI that takes high resolution B&W images allowing for a much more elaborate exploration at its closest approach of 425 km.

The unexpected discovery during that flyby is that Dinky has its own small moon. That moon, now dubbed Selam, is about 220 meters in diameter and seems to be orbiting its parent in some form. An estimated 15% of all asteroids are binary systems like this one.

Asteroids can be weird...

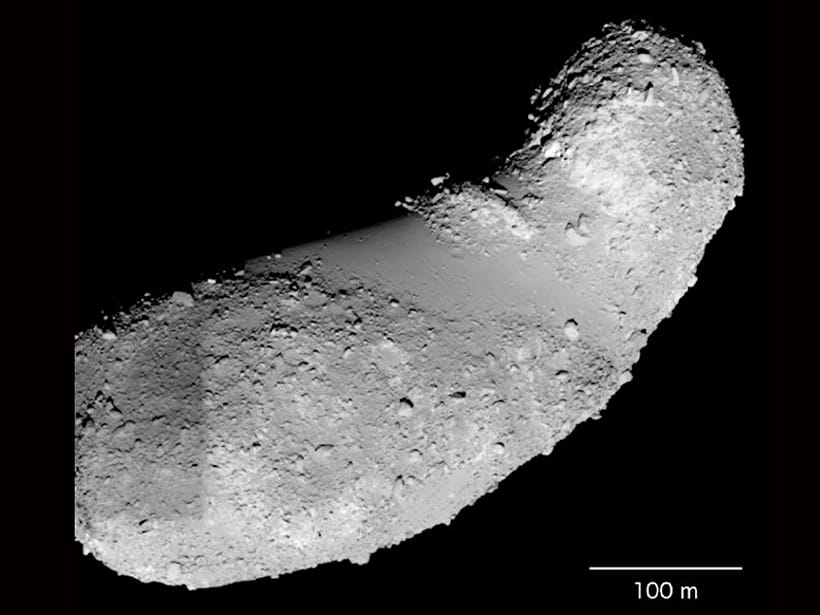

When the OSIRIS-REx mission approached its target Bennu, it expected to find what the mission team was calling 'beaches', large areas of fine-grained materials without obstructions somewhat similar to what the Japanese Hayabusa mission had found on its visit to asteroid Itokawa. That asteroid had an elongated bean shape with what appears to be fine sand beaches in its middle portion.

When OSIRIS-REx found its way to Bennu and started mapping its surface, it found a totally different environment including a complete lack of beaches. The massive rock you see on the image below was called Benben Saxum, it has a width of ~60 meters and a height of about 30 meters.

We won't know exact size, rotation, tumbling, surface conditions or exact composition until we get actually there. And that is only part of the challenge.

Launch schedule & orbital dynamics

The various agency missions had a specific launch target, known years in advance and used for detailed and deterministic planning. The whole mission and spacecraft design are optimized for that target, but that approach also introduces a significant amount of fragility.

The orbital dynamics of targeting a very rapidly moving tiny object that is very far away makes for a complicated puzzle. Pretty much everything we're interested in co-orbits the sun, which means we need to wait until it is close enough for the trajectory to close. If you launch a couple of days late, you might miss your target entirely unless you wait until it comes back around. If you don't have enough delta-v as margin, you might not be able to make it at all.

Having a fixed set of targets might mean that you can't fly your mission at all, which is what happened with the NASA Janus mission. That spacecraft was built and ready for launch, but it was manifested as a secondary payload on a rocket and other mission that was delayed. That delay made it impossible to reach its original targets or any other targets that are of similar interest. The spacecraft has been put in cold storage.

Asteroid Leaderboard

Rather than have a spacecraft that can only go to a single target if it launches in a narrow window, we designed our mission and our spacecraft to be flexible. Our asteroid leaderboard is a weighted list of targets we like, designed around a mixture of being reachable (flexible launch window/delta-v/time of flight), 'easy to excavate' (large, slow rotation, not tumbling) and attractive (regular visits possible, right spectral profile).

The board has several hundred asteroids on them at the moment, with more added every day as new discoveries happen. Our top 10 has remained fairly stable for our first mission, but we want to retain that flexibility and be able to choose a different target all the way up through our spiral to Earth escape.

"A poor man's guide to deep space" is a series of posts about our roadmap, approach to mission and spacecraft design to try and explain how we are tackling running missions at a fraction of the agency budgets.